Ingestion is the most intimate form of aesthetics.

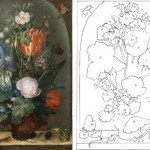

To destill a still life one must first identify and index, collect, breed and cultivate all the living life depicted (plants, lizards and insects) in a still life painting. At a moment in late spring, the equal parts of real specimens to painted specimens are distilled into a vital drink.

The departure point for the work DeStilling Still Life emerged from our research into the links between the floral still-life paintings and the cut-flower industry. For our very first distillation in 2007 we used  Bloemen in a Vase (1617), by Jan Brueghel the elder (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen) based upon an inventory of the encyclopedic array of flowers depicted in Brueghel’s painting.

The distilling apparatus is the vehicle to transport our studies and artistic ideas. We like to think of the distiller as an analogue machine, acting as a hydraulic computer processing all the still-life ingredients. The ingredients are not only what is seen in the image, but also the painting’s relational fabric such as the allegorical subject of passing time and the moralising christian symbolisms but not least the complex web of economic and social ecologies.

TANGENTIAL THOUGHTS

The development of the still-life in the early 1600s was synonymous with the increasing urbanisation of Dutch and Flemish society. Arguably, the emphasis on commerce, trade and market speculation in buying and selling abstract commodities was the ‘bulb’ of high capitalism. Tulips often appear as the prima donna of flowers in Netherlandish floral still-lifes.

On the one hand, still lifes drew attention to the carnality and decay of life and the stern judgement of God, however, the painted depiction of these priceless, unobtainable luxury goods (especially tulips) in still-lifes is itself materialisation of an (im)material desire, the tulips especially are  a brand of something that can be never fully grasped: possessing a still-life demonstrates the ability of an individual to attain a God-like

power through the merits of his entrepreneurial skills and associated wealth. Perhaps the presence of a rare tulip in still-life paintings is the first instance of branding. Tulip mania (1633-37), was the first time investor invested in something they had no direct connection to, the capital economy attained an increasingly abstract yet pervasive role in the political and cultural fabric.

BREAKING-DOWN THE CULTURAL IMPASSE

By re-assembling the still-life, we want to playfully challenge the historical and contemporary humancentricsm — the intervention of humans and how we have, over many centuries, culturalised nature. The Netherlands, in particular, is a country which is almost completey culturalised. It’s a territory that exists with thanks to the feat of human engineering and control. Agriculture is a simplification of the nature it has ‘reclaimed’. In a way, our cultural relation to nature is a kind of disembodied agriculture.

Concept and idea: Wietske Maas and Nikolaus Gansterer

Year: 2007, 2008 & 2010-11

Locations: Museum Hessenhuis, Antwerp, 2007, KAAP, Utrecht, 2008; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 2010-11

De-Stilling-Still-Life [website]